DEM BONES, DEM BONES, DEM DRY BONES

OK, so, the Disrespecting of the Bones. Now that was pretty bad, I think. You see, Myrtle is a bit of a fanatic about colonialism and the way indigenous and native peoples are always treated by their conquerors.

When she found out our guide was a full-blooded Inca, she was a bit giddy with glee, to tell you the truth.

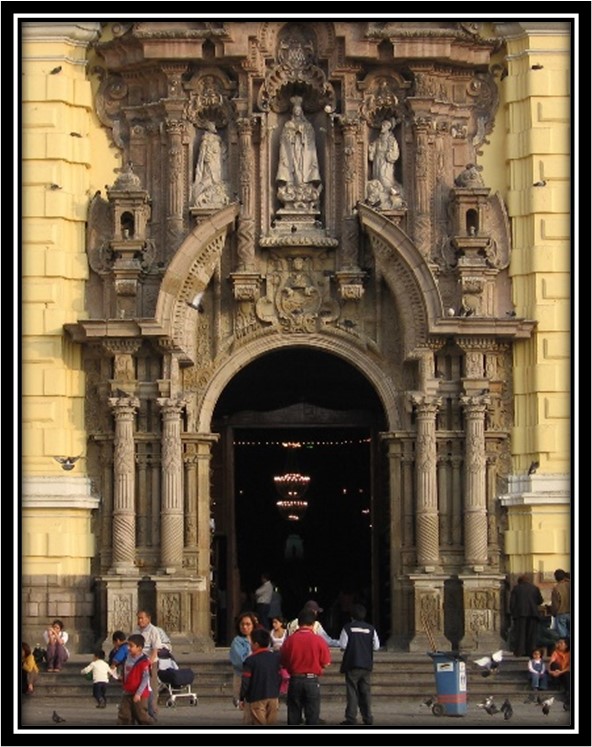

The day we were in Lima and visited the Franciscan Monastery, a wedding was taking place there, and Myrtle scrutinized the party carefully and whispered to me that they were descendants of the Conquistadores.

I think that almost immediately her busy little mind was trying to figure out how to get back at them, which sort of distracted me from all the fascinating facts our guide was telling us about this huge old monastery complex, which, I do agree, despite its provenance, was amazing.

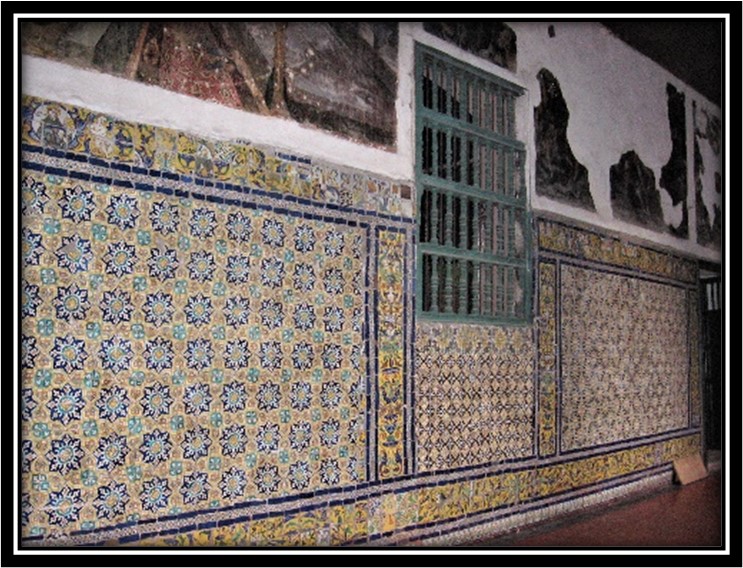

The Monastery mostly dates to 1650 and is a famous example of the style called Spanish Baroque. Most of the stone floors and mosaic walls are original, as is the exquisite old convent library.

In the 1990s Spain spent seven years restoring deteriorating parts of the Monastery. Wow!

Most intriguing to me was the reason why the building does not crumble: egg whites from birds’ eggs were mixed with sand and pebbles, and it is the birds’ egg whites that hold it all together! I did wonder just how many poor little bird mommies and daddies were robbed during the years of construction.

Anyway, the government made it illegal to damage or tear down original Inca structures, including homes, and they were rewarding Peruvians with deed titles to land if they agreed to establish an authentic Inca residence and live the way the Incas had lived. Once we saw how the Incas lived, I do have to tell you I wondered how many takers there would be, especially since Inca houses can be passed on to the next generation but cannot be sold or turned into commercial properties like a hotel.

Our guide took us down into the catacombs where the dead of Lima – Spanish descendants only – were buried with limestone for 300 years, an estimated 25,000 bones. I was shocked to see that all the bones were laid out in designs like flowers, with long bones spread out in fans around skulls and pelvises.

When I asked our guide why that was, she airily replied, “Oh, the workmen were just having a bit of fun because only people of Spanish descent could be buried here.”

While I was talking to the guide, I noticed Myrtle was staring intently at the bones.

Then as our guide led our group back up the crypt steps, Myrtle snatched up her walking stick, deftly unscrewed the cap and pulled out the two extenders, making the aluminum stick about eight feet long.

Quick as a wink she reached over the metal barrier and snagged a pelvic bone, which she expertly dragged over to where there were piles of mostly intact hand bones.

With a dexterity I would never equal in a million years because I would be petrified with indecision, she somehow maneuvered that captured pelvic bone into a position where a middle distal phalanx of one hand was sticking straight up at the coccyx of the captured pelvic bone. Then she emitted a satisfied “Ha!”

You will notice that out of respect for your delicate sensibilities, dear reader, I am using scientific anatomical terminology to describe the quite uncouth gesture Myrtle had created. Please, no need to thank me; you are entirely welcome.

Anyway, my shock left me momentarily speechless and unable to move, until I noticed that a young boy from the wedding party had come partly down the steps and not only had seen what Myrtle did, but quickly understood the gesture she had created. He started to yell and point at her.

Having experienced the unpleasant consequences of guilt by proximity, I quickly scooted over to the other side of the crypt where I became greatly interested in a particular configuration of bones, while two burly guards came clattering down the steps.

The boy haughtily reported to them what he had seen Myrtle do.

Unknown to all of them, Myrtle speaks excellent Spanish and followed the conversation closely even while she managed to retract her walking stick to its original size and commence gazing reverently down at the bones, then lean elegantly on her walking stick.

When the guards started to confront her, Myrtle turned her innocent big blue eyes on them and asked in her best little girl voice, in English, “Sir, may I ask why that one bone seems out of place, right there, the one next to the finger. Shouldn’t that bone be over there with all those other bigger bones that look like that? I think it is disrespectful that it is out of place like that. Don’t you think so? What can be done about that?”

And she continued in that vein, all the while batting her eyes at the guards until one of them finally told her, in English, that he would personally see that the bone was placed appropriately.

Myrtle promptly squealed a little and giggled and kissed him on the cheek, which so flustered him that he stood there stupidly while she regally ascended the stairs.

The young boy, who obviously had not followed the English conversation, gaped after her. I took that opportunity to quietly move up the stairs also, at a discreet distance from Myrtle.

Once we were safely out in the Plaza and swallowed up in the crowds, I pointed out to her the police water wagon nearby, with three policemen standing at attention behind their shields.

The National Police Water Wagons are basically giant water pistols that shoot out powerful streams of water for crowd control or apprehension of criminals.

As we hurried to catch up to our group, I sort of hissed at Myrtle, “Were you trying to get us hosed? You know I love water parks, but the thought of flying across Plaza Bolivar on a jet of water does not appeal to me when I am wearing my best hairdo, especially if I should land in front of the Cathedral as the Cardinal is finishing Mass! I would love to meet the Cardinal, but only if my hair is having a good day.”

But Myrtle just smiled serenely and walked on with a smug bounce in her step.

These weren’t our only encounters with bones on this trip, but none of the other encounters presented such a fortuitous opportunity for Myrtle to express her anti-colonial sentiments. Also, most of the other human bones we saw were Inca bones.

For example, we visited the largest cemetery of the Incas, in Pisac, where over 2000 mummies were found and removed. When they were buried, the bodies were fitted into a tight fetal position and placed in a hanging basket facing east. Altogether over 20,000 people were buried in Pisac, often near Huacas, which are memorial objects to be revered, like immense rocks.

As we walked the ruins, our guide told us the history of Pisac, which was an important military base where 5000 people lived in the earliest years of the Incas, the 1300s and 1400s.

Historians date the beginning of the Inca Empire to the 1430s and 1440s, and we know that the Inca Empire was built on previous cultures, like the Paracas, who were highly skilled pottery makers, which may be why most of the construction in Pisac is stone with clay between the stones, unlike the later Inca structures where the stones are fitted so expertly no clay is needed.

Since the Incas allowed conquered peoples to retain their own religions and worship their own gods, there was quite an interesting assortment of deities in Inca times, it seems, including the Decapitator God – yikes!

But as we learned, human sacrifice was definitely a common practice among the Inca peoples, so I guess it makes sense they would worship a god that helps them chop off someone’s head efficiently.

As we passed what looked like small mountains of little bones, I asked the guide what those bones were; and I got quite an education, dear readers!

It seems that the thousands of small animal bones found at Pisac were from guinea pigs.

Obviously being a guinea pig in Inca times was no fun. The priests would capture anywhere from 100-500 of the cute little critters, adorn them with tiny earrings and necklaces, and sacrifice them one after the other to appease the gods or solicit their help.

Then there would be a mass burial, sometimes with the little critters wrapped in tiny blankets. As we walked around the bones, Myrtle snatched up a few wildflowers and placed them reverently on some of the bones. Since the Incas believed in reincarnation, I wondered how many humans had to be reincarnated as guinea pigs to keep up with the demand.

The humans were buried with pottery, tools, foods, and everything they would need in the afterlife, as we had seen in the National Museum of Archeology and Anthropology in Lima, that sprawling, well-maintained complex that once belonged to the lover of Simon Bolivar, and where he stayed when in Lima.

In the Museum we saw the mummy of a 45-year-old man who lived over 1000 years ago, an important ruler of the Lima tribe. He was in his basket of reeds, buried with foods, weapons, pottery, etc.

His basket was hanging from the ceiling in an alcove and looked for all the world like a gigantic oropendola nest, that bird in the Amazon that builds those amazing gourd-like nests that hang from the trees like huge ornaments.

I was thinking that the early people in South America must have copied the oropendola bird to build their hanging burial chambers, an interesting twist, I guess, since the bird uses the nest for new life and the humans use the nest for death. Perhaps that was a message about reincarnation?

As we passed the hanging nest casket, I saw Myrtle lagging behind the group, so of course I felt I had to watch her closely to avoid another disastrous episode with bones.

But all she did was go up to the hanging gourd casket, set it swinging gently, and croon, “Lullaby and goodnight, with roses bedight; With lilies o’er spread is baby’s wee bed. Lay thee down now and rest; may thy slumber be blessed. Lay thee down now and rest, may thy slumber be blessed.”

I swear, dear reader, I thought I would cry right on the spot, it was that beautiful.

Then of course Myrtle had to ruin it by pointing out the nearby mummies of a woman and baby with a guinea pig. The sign, which Myrtle kindly translated for me, told us they had been a sacrifice, possibly to the shark god, and were buried together.

Our guide had earlier informed us that nearly everything was worshiped by the peoples who inhabited these lands, and that babies were routinely tossed into the sea as a gift to the shark god. “But don’t worry,” she said. “It was all very humane. The babies were given a hallucinogenic drink prior to being thrown into the sea.” Hmmm. OK, then.

The Incas held religious festivals every single month, in addition to any needed sacrificial days, so I guess it was not a good idea nor conducive to a long life to be a guinea pig, a baby, or a young virgin in those days.

The Peruvian hairless dog, or Inca dog as it was sometimes called, seemed to be doing OK, maybe because it was just too ugly to be of interest to the gods? There were several being used as guard dogs around the Inca burial mounds where excavation was in progress, and I had to restrain Myrtle from approaching one and trying to pet it, because our guide had told us the dogs can be fierce. Myrtle, of course, wanted to test that theory.

Fortunately, I was able to distract her by asking her to tell me more about her newest great passion, Manuela.

To be continued…